While we were in São Paulo, I couldn’t resist the opportunity to visit the Museo Judaico de São Paulo (Jewish Museum). The museum itself is housed in a former synagogue, Beth-El Temple, dating back to 1928 and consists of four floors. The ground floor has a permanent exhibit called “The Jewish Life” that portrays the many holidays, food, and life cycle rituals of the Jewish people. Both the mezzanine and 2nd basement have temporary exhibits featuring local artists. When we visited, one floor featured art by Lasar Segall, an impressionist avant-garde artist from Vilnius who migrated to Brazil in 1923. Another temporary exhibit featured the art of Hanna Brandt, a little-known German Jewish artist who resides in Brazil and whose work spans a 60-year period. What we really came for, though, was the exhibit on the first basement floor titled “Jews in Brazil: Interwoven Histories.” The largest Jewish archive in Latin America is on the third basement floor and, of course, it was closed the day we visited. The next time we visit São Paulo I intend to make an appointment ahead of time to learn all about the archive.

In addition to being housed in a lovely building, the “Jews in Brazil: Interwoven Histories” is packed with information. Everything is available in Portuguese and English, which made it a very enjoyable experience. I can’t possibly summarize everything we learned, but below are my top five favorite facts:

- The first openly Jewish community, synagogue, and rabbi in the Americas was in Brazil thanks to the religious freedom provided by the Dutch. (From 1630-1654, a small portion of northeastern Brazil was Dutch Brazil.) Most importantly, this was an opportunity for Jewish people to escape the Portuguese and Spanish Inquisitions. After the Dutch lost their war to the Portuguese in 1654, everyone was expelled from Dutch Brazil, including the Jewish community. The street where the synagogue was housed in Recife was called the Street of the Jews but once the Portuguese took over it was renamed Street of the Cross and then Street of the Good Jesus. (It’s still called that today.) After expulsion, most of the Jewish community from Dutch Brazil ended up in New Amsterdam, now New York. However, one ship, landed in Jamaica.

- The Portuguese Inquisition wasn’t quite as harsh in Brazil as it was in Spanish-controlled colonies in the Americas such as Cartagena, Colombia. Still, people were arrested, shipped to Lisbon, and tried for all sorts of crimes, which created a culture of fear. Approximately 1,100 people were arrested in Brazil, half were accused of Judaizing, and 25 died by being burned at the stake.

- Fast forward to 1820: Belém (of the Pará state in the northeast) was the home of a significant Jewish community in Brazil. Many of these Jews were Moroccans impacted by the wars between Morocco and Spain during that time.

- In the 19th and 20th centuries, many Jewish immigrants all over the world worked as peddlers. In São Paulo, they were called “clientelechik” a Yiddish-Brazilian hybrid word.

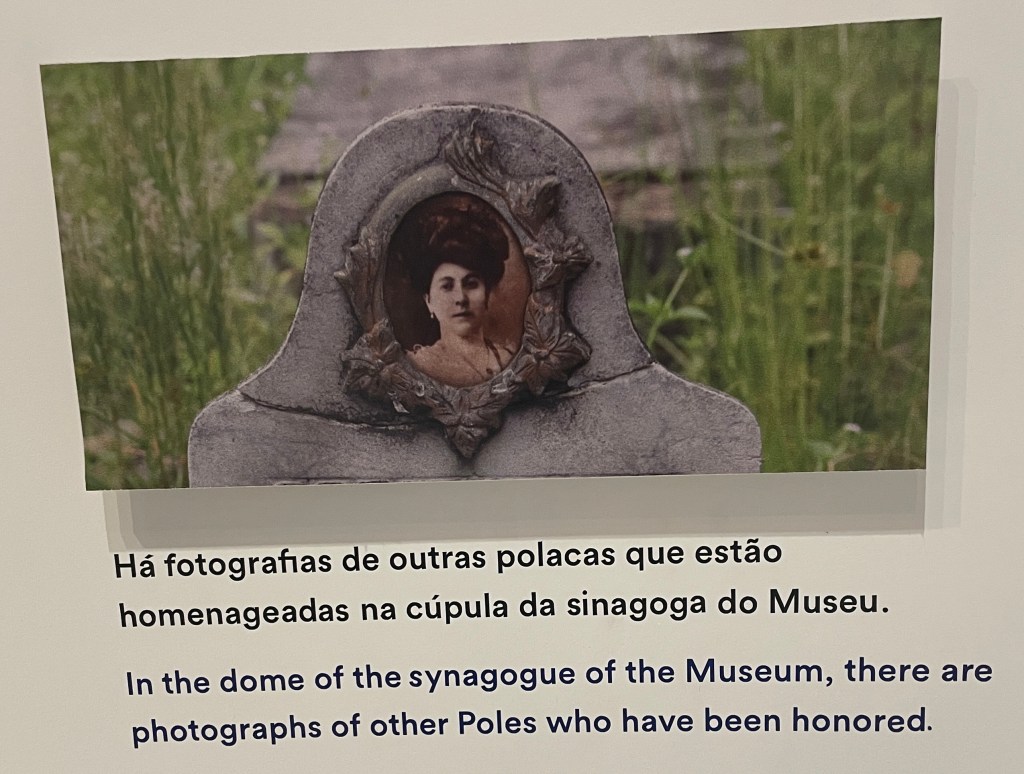

- At the end of the 19th century, many Jewish European women migrated to South America by promises of work but were trafficked into prostitution. They were called “Poles,” even though not all of them were Polish. They created their own mutual assistance organizations, the first of its kind in Brazil, throughout the country. Though local Jewish communities rejected these women because they were prostitutes, they helped each other, maintained their Jewish roots, and improved their local communities.

Below are some photos from the exhibit.

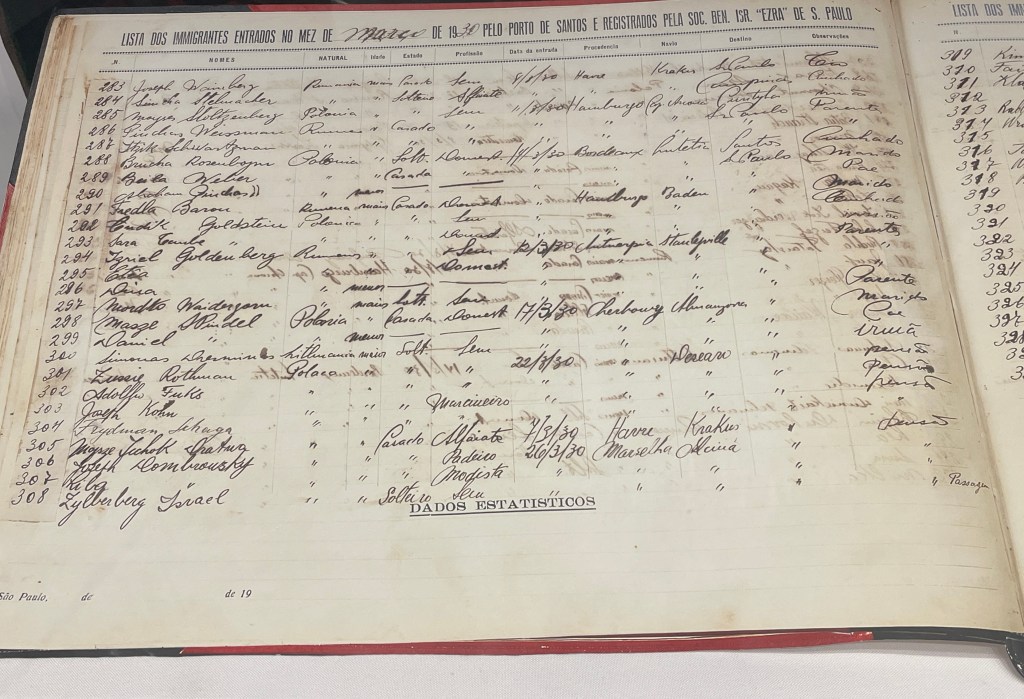

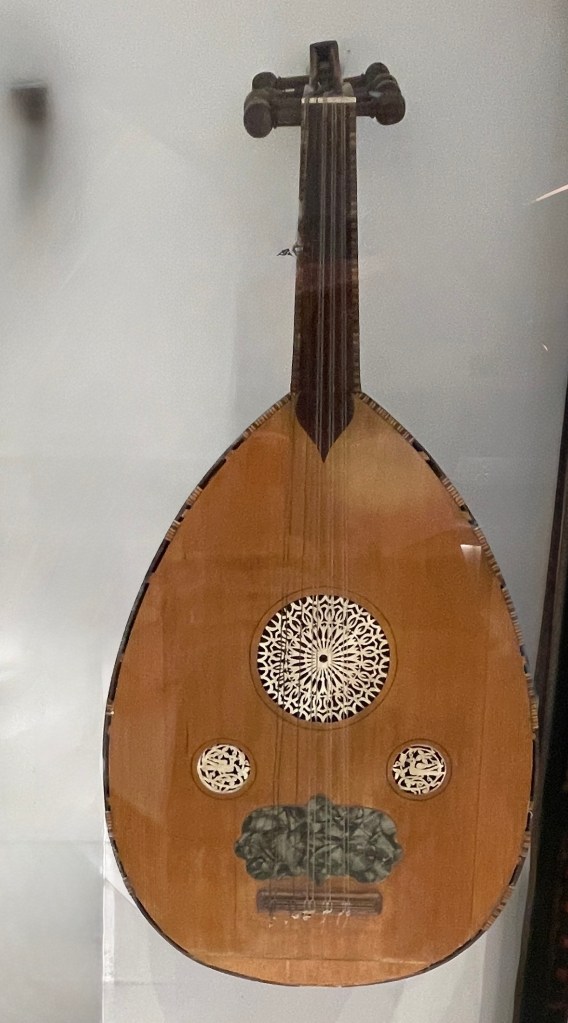

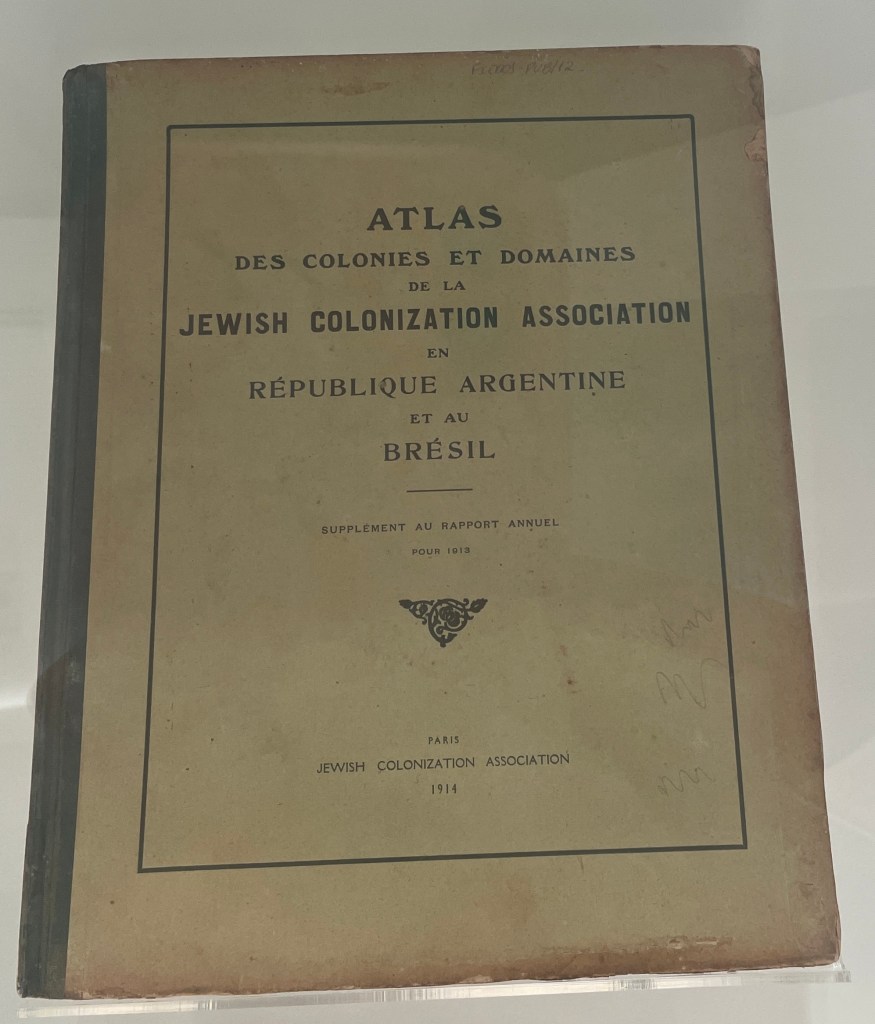

First row, left to right: a registrar of immigrants from 1930; Jacob Haber’s lute from Syria; a directory of Jewish organizations and people in Argentina and Brazil from 1914.

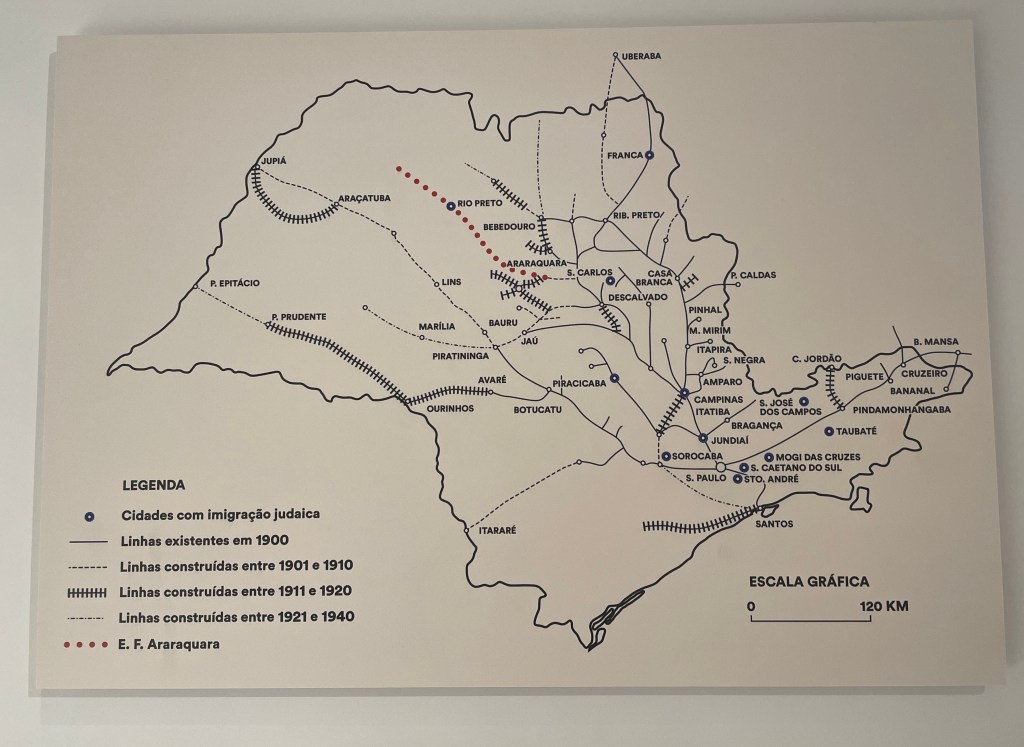

Second row, left to right: a map of Jewish migration within Brazil over the years; a poster from a play in Yiddish; a photo honoring a “Pole” woman.

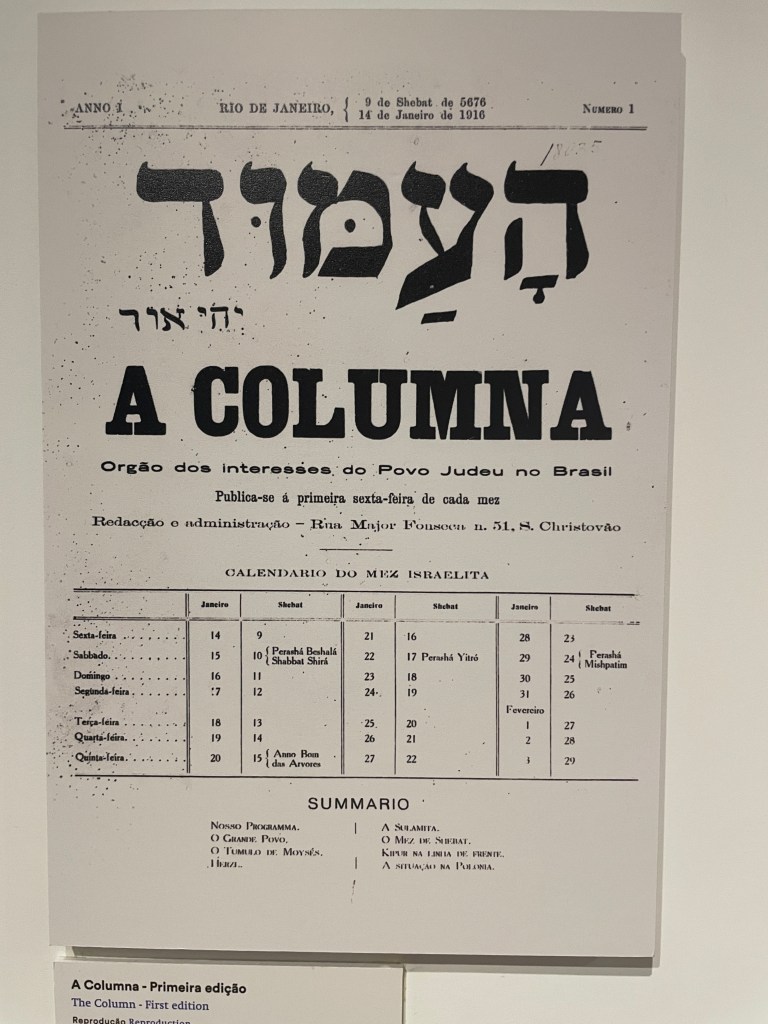

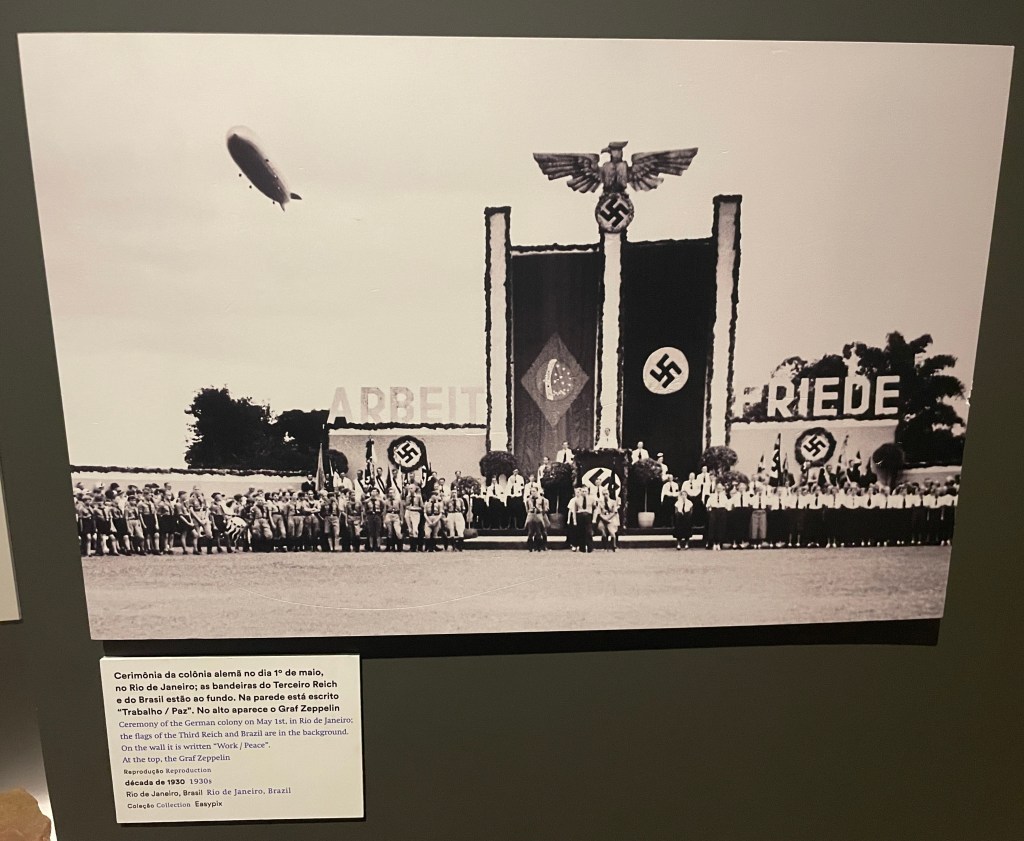

Third row, left to right: reprint of the Jewish newspaper “The Column” from Rio de Janeiro; a photo of a pro-Nazi rally in Rio de Janeiro in 1930.

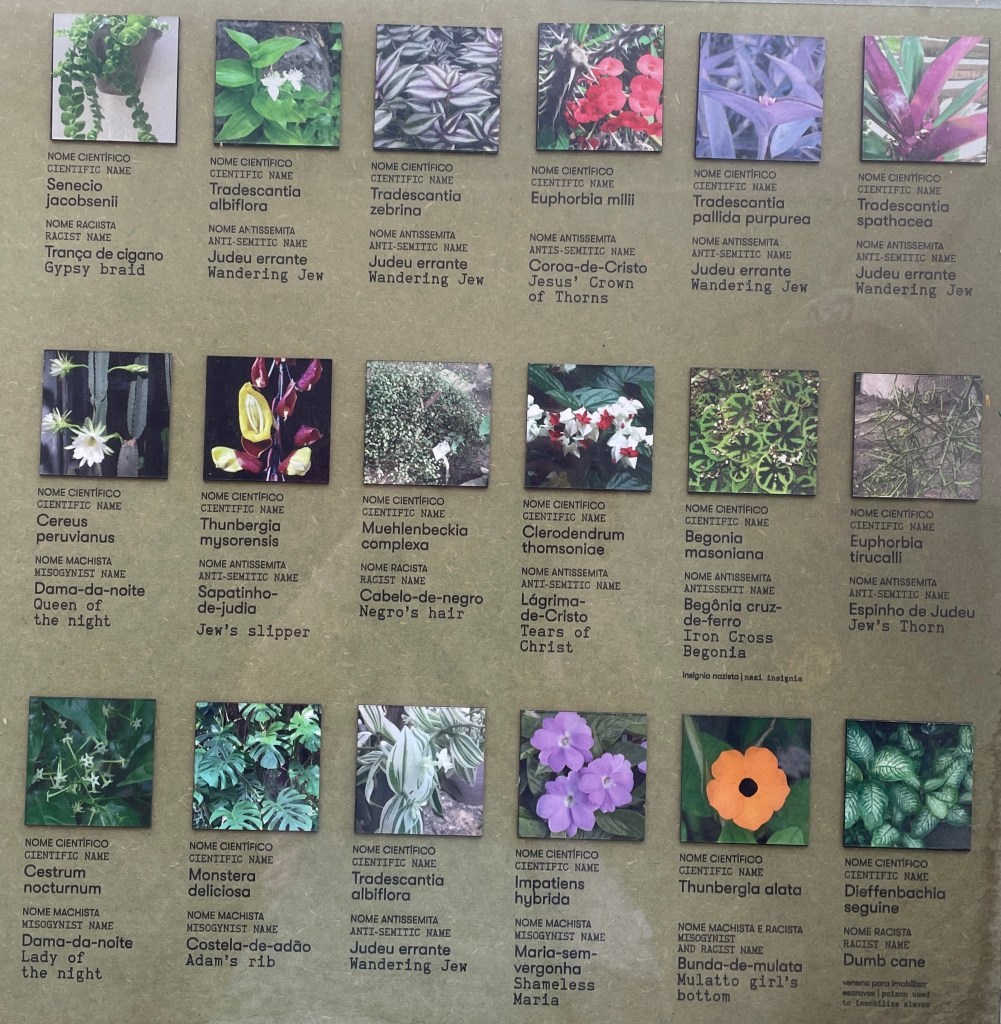

As we exited the museum, we noticed a small garden. The plants have names that carry misogynistic, antisemitic, and racist connotations. The garden was a reminder to take a moment to reflect about the banal ways language informs our culture and understanding of the world. (A lot of these plants are considered weeds, too, which is particularly troubling.) I encourage you to click on the photo to enlarge it, read the names, and consider how it impacts your worldview.

Besides the Jewish museum, I was also excited for all of the fresh produce available in Brazil, especially the fruit. When Adam researched places for us to explore in São Paulo, he added the Mercado Municipal to our list. In this repurposed building, vendors sell spices, cheeses, cured meats, pickled everything, and fruit. One of the ways the vendors encourage people to purchase their produce is to wave you over and just give you piles of fruit to taste. It’s a little overwhelming and, at one point, Adam asked him to stop because it was just too much sugar. The prices are inflated, but we bought a beautiful little plate of fruit to eat for breakfast.

The most surprising fruit we tried was cashew. I love cashews and was very surprised to learn you can eat the fruit as well. In Brazil (and maybe in other parts of the world like India), the cashew fruit is most often juiced. We tried the juice and enjoyed it, but the flavor of the fresh fruit was incredible. It was so tropical yet subtle with an almost milky texture but not too thick. We didn’t really chew the fruit, just sort of sucked on the juice, so it made sense that it’s most commonly available in juice form. Achachairu is soft and juicy like a lychee, but very tart. (Adam ate most of them.) Sapodilla has a grainy texture and a very mild flavor. I grew up eating custard apple but haven’t had any in years. They’re similar to a soursop but sweeter. Cajá has a very thin skin and the fruit inside has a bright, tropical flavor. We tried these in Costa Rica, but I forgot about them until we saw them at the market. Persimmons are my favorite autumn fruit and I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to try perfectly ripe ones. Compared to the rest of the fruit they were the most bland, which speaks to how flavorful everything else was.

After all that fruit, we needed to eat real food. The second floor of the marketplace has plenty of restaurants, many of which serve mortadella sandwiches. (Apparently, these specific mortadella sandwiches are a specialty in this market and are unique to São Paulo.) Adam ordered one with mortadella, pepperoni, grilled tomato, and smoked paprika aioli. I didn’t bother asking if there was any gluten-free bread. Instead, I ordered a Brazilian specialty: bacalhau. Bacalhau is salted cod that is rehydrated and then flaked. The taste is similar to saltfish used in Jamaican cuisine. This particular fish was served with crispy potatoes, olives, grilled onions, a hard-boiled egg, and excellent olive oil. Delicious!

While we were with some of Adam’s cousins, we had a chance to eat Brazilian food from the northern state of Bahia, known for its Afro-Brazilian culture and West African influence. To start, we ordered acarajé: fried balls made from black-eyed peas or cowpeas that can be filled with all sorts of goodness. The ones we ordered came with a side of shrimp, a tomato-onion relish, and manioc, a paste from cassava. We also ordered the roasted crab meat that was some of the best crab we had had in a long time.

The four of us shared two mains. First, was the fish and shrimp moqueca (left photo). Moqueca is a coconut and tomato-based stew filled with all sorts of seafood, meats, or veggies. Adam and I had both tried moqueca at a restaurant in Los Angeles and loved it. This moqueca, though, made the other one seem very bland. Bobó de camarão, the other main we shared, was new to us (right photo). It looks similar to the moqueca, but it’s thicker and more reminiscent of a gumbo. We ate both stews with rice, a thickening sauce made from cassava (similar to how okra can be cooked to thicken a gumbo), and farofa or cassava meal that has the texture of thick breadcrumbs. (In the photo on the right, the thickening sauce is in the red bowl and the farofa is in the white bowl.)

As if all this deliciousness wasn’t enough, we also ordered dessert and coffee at a place around the corner. Adam’s cousin encouraged him to order pastel de nata, a Portuguese pastry filled with an egg custard which he enjoyed (left photo). I ate the quindim, a coconut-based custard that happened to be dairy-free (right photo). I could have eaten ten of them! It was the perfect sweet treat.

Readers of the blog know we love East Asian food and since São Paulo has its own Japantown and Koreatown, we had to take advantage of the possibilities. Not only did I get to eat my weight in kimchi and Korean barbecue, but we also had a chance to eat sushi. Adam and I are spoiled being from Los Angeles, but these were valiant efforts that we appreciated greatly. The quality of the meat at the Korean barbecue was excellent and most of the sushi was pretty good. One strange thing about sushi in Latin America is that the fish options are typically limited to salmon, tuna, or white fish. We suspect that maybe other seafood is too expensive to ship, not popular enough to justify ordering, or maybe Latin Americans don’t like fishy-tasting fish. Either way, the sushi we had was the best since we began our adventure. One sushi dish of note is pictured below: a salmon roll with roasted cashew fruit. It tasted better than we imagined, but it was definitely an odd combination for a pair of Americans. (There were originally four pieces, but I made Adam try one first before I took the photo. Just in case you’re wondering.)

As we move north along the coast of Brazil, we plan to eat more traditional Brazilian fare and see what adventures await us. Be sure to like, comment, and subscribe to Traveling While Introverted so you don’t miss it!

Leave a comment