South America is known for containing some of the most famous ecosystems on earth such as the Amazon rainforest and the Pantanal wetland. That said, one of the continent’s most diverse biomes, as well as its most threatened, is the not as well-known Mata Atlântica (Atlantic Forest). Prior to European arrival to South America, this forest stretched from northeastern Brazil into western Uruguay, northeastern Argentina, and far-eastern Paraguay. Historically, it stretched around 390,000 – 580,000 square miles (1,000,000 – 1,500,000 square kilometers). After the Amazon, the Mata Atlântica was the second-largest rainforest on the planet and second largest forest in South America.

Today, the second-largest rainforest on earth is Africa’s Congo Basin and the South American continent’s second largest forest is the Gran Chaco. The Atlantic Foresthas lost around 85% of its original area since the Europeans arrived on the continent. It is one of the most threatened and endangered biomes on the planet. As a result, it only exists in small fragments in Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil. It no longer exists in Uruguay. That being said, it is still a phenomenally diverse forest with an extraordinary amount of endemic species (i.e. species found nowhere else). I was unable to hike the Atlantic Forest during our stay along the southeastern Brazilian coast, but I had my chance to do so in Rio at Parque Nacional da Tijuca (Tijuca National Park). The park surrounds the southwestern edge of Rio and forms one of the largest urban parks on the planet.

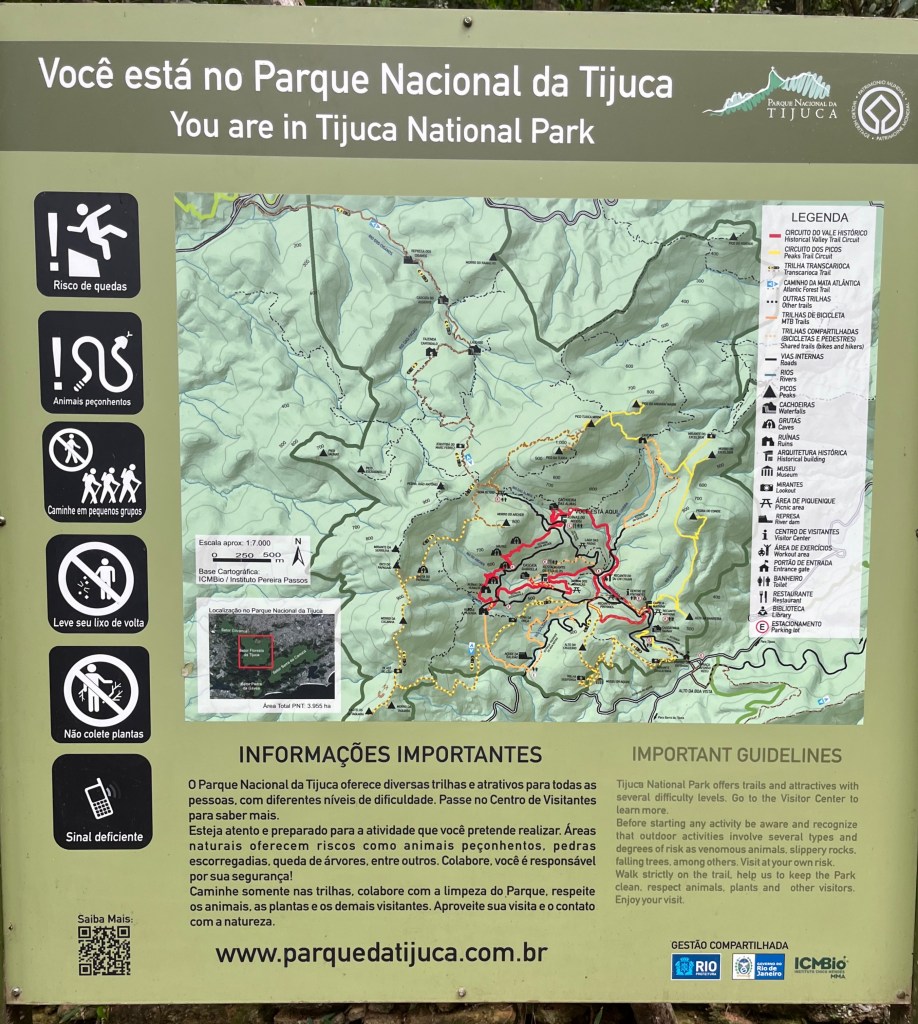

Yahm stayed back this time as it was going to be a long day. This is a massive park (covering 15.3 square miles (39.6 square kilometers)), so there was no way I was going to be able to see it all in one day. I really just wanted a taste of the Atlantic Forest while I was near it. The photo below is of a trail map showing the size of this park.

Tijuca is a great example of a tract of Atlantic Forest that harbors lots of species, including many of the biome’s iconic species, but that is not in perfect health and illustrates some of the issues affecting the system as a whole. This park was created out of necessity back in the 1860s. Previous decades of deforestation had dried out the rivers that fed the city and almost led to Rio becoming a drought-ridden hellscape. Enslaved Africans were forced to replant 100,000 trees and reforest acres and acres of steep mountains around Rio. (The enslaved Africans were later kicked out of their settlements in the mountains when the park became a tourist attraction.) While many of the trees, plants, and animals such as small reptiles and birds returned, larger mammals and reptiles did not. Decades of being hunted and killed off during the massive deforestation period had taken its toll on larger species. Park rangers and biologists have been slowly reintroducing larger animals to the park with mixed success. (You can read more about this and the history of the park here). Some of the major challenges to these reintroduction efforts have been stray dogs and roads that bisect the park leading to vehicle collisions. In general, there is a lot of difficulty in trying to reintroduce species with large ranges in an environment that is now hemmed in by urbanity.

From left to right: Roads bisect the park and provide transportation for visitors, but are a source of wildlife-vehicle collisions; a sign alerting visitors to the re-wilding efforts by park officials.

While this park may not be a full representation of what the Atlantic Forest was and can be in less-disturbed tracts, it is still a magical place. The forest’s canopy, composed of dozens of tree species, offered some wonderful opportunities to take some photos.

The cacophony of bird sounds was amazing. I identified 13 species during my half-day of hiking. That is a lot but paltry considering that hundreds of avian species call both the Atlantic Forest and Tijuca home. I heard Rufous-browned Peppershrikes, Rufous-martined Antwrens, Chivi Vireos, Gray-fronted Doves, Yellow-olive Flatbills, White-necked Thrushes, Plain-winged Woodcreepers, and Plain Parakeets. I also heard Channel-billed Toucans raucously calling and captured it as best as I could in the video below.

I was also able to capture a video of a Rufous-tailed Attila hanging out on a tree trunk and vocalizing.

My best birding experience on this hike was when I found a group of male Swallow-tailed Manakins. Manakins are the American Tropics’ version of New Guinea’s Birds-of-paradise made popular by the Planet Earth docuseries. Most species of manakin males do not perform solo dances. Instead, they engage in choreographed dances to attract females that can be spectacular to behold. These particular males were calling to each other. Maybe they were looking to attract a female or just communicating back and forth. Because I was having a hard time seeing the birds, I used my Merlin app to playback the calls of one of the males I had recorded. This drew a few individuals close enough to me to capture photos and videos. I normally would not do this as it is can confuse animals, but I broke my own rules this time.

This photo shows just how close I was able to get to one male manakin in particular.

The hike itself had its share of steep climbing. While the weather that day was relatively cool with cloud cover, the intensity of some of the inclines still made me sweat. The inclines provided some amazing views of the park and the surrounding mountains.

The Atlantic Forest is also one of the wettest biomes on earth and stores water incredibly efficiently. Creeks, waterfalls, and huge ponds provide water for wildlife, plants, and further down the mountain the city of Rio de Janeiro. (This is why this place was reforested and why we all need to preserve forests globally.)

Tijuca houses ruins from when communities of enslaved Africans lived in the park. As previously mentioned, enslaved Africans were booted out of the park after helping build it (a story far too common in the Americas as a whole). The ruins were haunting not only because of what they used to be, but also because the forest had reclaimed its space. A favela of (mostly) Afro-Brazilians exists in the farther reaches of the park. (I did not visit the favela.)

Plant life in the park was wondrous. There were beautiful flowering and fruiting trees, and cool undergrowth species that showcased the incredible diversity of the forest.

Top row, left to right: this flower (one of many around the ruins) was attracting tons of wasps; the Atlantic Forest has several native species of bamboo (though no pandas); this palm species has sharp spikes to protect its coconut-like fruits from mammals and to allow birds to pollinate it when its fruits are ripe. (These spikes were also utilized by the Indigenous tribes to make the hollow-tips for poison darts.)

Bottom row: two photos of the same plant; this plant had sharp spikes that pierced its own leaves to protect the precious little fruits below. (I got pricked taking a photo.)

Before I sign off, I want to share my favorite wildlife interaction in the park. I snuck away from a large group of tourists and climbed to the top of a rock outcropping. As the group passed, I spotted a troop of Brown Capuchins that were in the trees. They were so close, I was able to view them without binoculars. It was thrilling and a little scary because capuchins are smart and can get aggressive if they feel cornered. Luckily, this troop was not phased by my presence.

The entire hike through Tijuca was amazing and exhausting. I hiked several miles and spent close to seven hours in the park. I thoroughly enjoyed it and would love to go back not only to Tijuca, but to other tracts of the Atlantic Forest.

So long from both Rio de Janeiro and Brazil. Don’t forget to check out other posts from our time in Rio as we head to our next country. We hope you continue to join us on our adventures. Be sure to like, comment, and subscribe to Traveling While Introverted so you don’t miss it!

Leave a comment