Among the world’s most economically consequential linkages, the Panamá Canal lies within the metropolitan area of Panamá City. The canal runs for approximately 51 miles (82 km) through the narrowest part of the country. It connects the country’s Pacific Ocean coast with its Caribbean Sea coast. In its middle course, it rises above sea level and runs through the mountainous middle of the isthmus before meandering back down to the gentle coastal plains on either side of the country. It is a true marvel of engineering. By connecting the Pacific with the Atlantic (via the Caribbean Sea) it cuts the journey between the two major ocean basins by over 2,000 miles (over 3,200 km). Most importantly, besides saving ships both fuel and time, it helps prevent ships from having to risk sailing through the Drake Passage along South America’s Cape Horn. The cape, at the southern most tip of the South American continent, is surrounded by some of the most dangerous waters on the planet. Monstrous waves can easily tip over a cargo ship and have shipwrecked countless voyages throughout history. The canal provides both a shortcut and a safety valve for global shipping and makes it one of the most heavily-used waterways on the planet.

The canal has a complex history, one that is fraught with death, intrigue, power, and geopolitical consequence. The idea to cut through the Isthmus of Panamá dates back to when the Spanish first explored and colonized the region in the early 1500s. However, the French were the first to begin the process of breaking ground and constructing the canal in 1881. By 1889 investors pulled out of the construction due to engineering issues and a high level of worker mortality caused mostly by tropical diseases such as malaria and Yellow fever. Rights-of-ways and land along the canal was purchased from France over the course of two years (1897-1899) under United States President William McKinley. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt began constructing the canal.

While construction was underway, the U.S. government helped Panamanians break free of Colombia (which claimed the isthmus at the time) and gain independence on November 3, 1903. On August 15, 1914, the canal was formally opened and the United States controlled the canal and the 10 miles of land to the east and west of the waterway along its entire length. This area became known as the Panama Canal Zone. From 1903 until 1979, the U.S. government treated the Canal Zone as a military asset and excluded Panamanians from living and working there. U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Panamanian President Omar Torrijos signed a series of controversial treaties that year that allowed Panamanians to live and work in the Canal Zone and also promised that the canal would be handed over to the Panamanian government in twenty years. In 1999, as promised, the United States gave the canal to Panamá to manage and control as well as defend it. Panamá does not have a formal military and relies instead on a network of militarized police forces for security, meaning it is vulnerable to potential military actions by a larger nation. This is just a summary of events and I encourage readers to look deeper into the history of the canal.

While Yahm and I were in Panamá City, we toured the canal. Panama Canal Tours offers both a full-day tour option (which lasts up to 12 hours) where you sail from the Pacific side to the Caribbean side and then are bussed back to Panamá City. Or, you can take the half-day tour (which lasts up to 6 hours) and transports you to the halfway point of the canal before you are bussed back to the city. We chose the latter option.

The canal never closes and every ship that enters on either the Pacific or Caribbean side has to pay a toll to utilize it. The canal’s middle section, known as the Culebra Cut, is narrow and is a chokepoint for traffic. Therefore, to help facilitate ships through, there are two shifts of traffic per direction (four total) during a given day. The timeframe of when north- or southbound traffic flows during the day can shift; therefore, if you miss your chance, you have to remain parked outside the canal to re-enter the following opportunity. Our ship, and others in the Pacific, had the first shift of northbound traffic which was early in the morning. We arrived at the entrance of the canal before 7 a.m. waiting in line with other large vessels to start the journey.

Before any ship enters the canal, they have to allow a designated pilot to board the ship and take control during the entire length of the journey. It was amazing to behold, as the pilot will board your ship like a pirate.

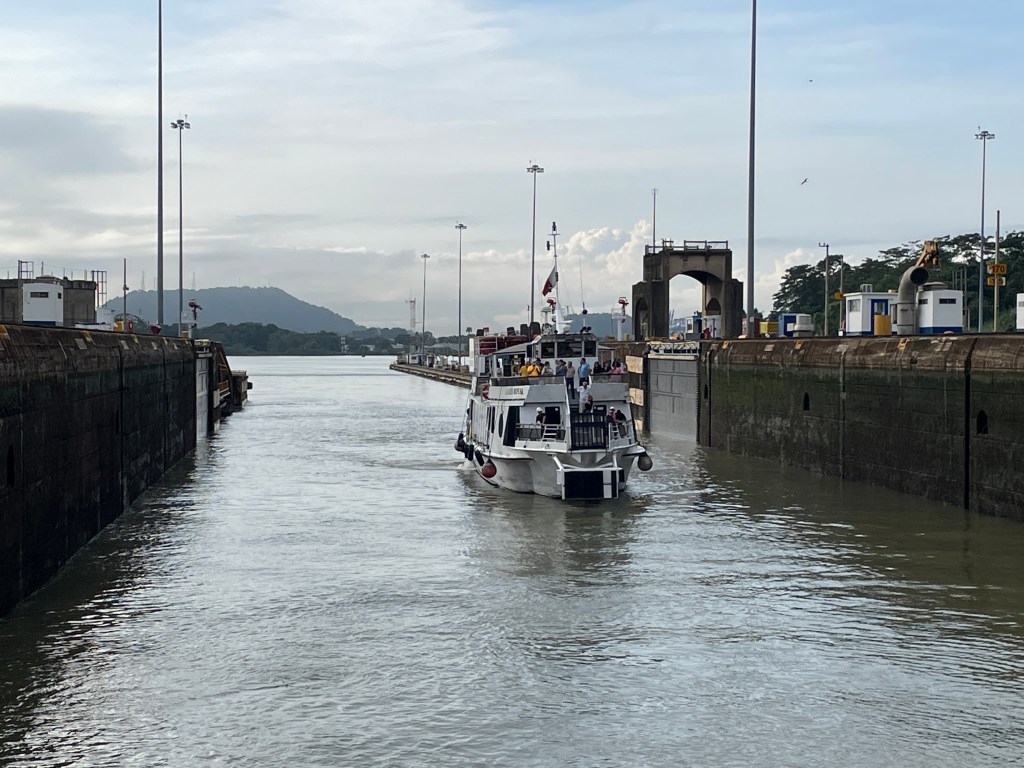

Once you have your pilot on board, you enter through the first in a series of locks. The first one is called the Miraflores Lock. Each lock is named after the town that used to exist in the area prior to canal construction. (The basic mechanics of the locks are explained below.)

The canal is like a river with locks that operate like water elevators. The tallest part of the canal is Gatun Lake (close to the Caribbean coast) which holds the largest reservoir of fresh water as well as being its heartbeat. The lake, which sits approximately 85 feet above sea level, fills up with rainwater that is pushed to the ends of the canal through gravitational intervention. Because the entrance and exit of the canal is at sea level, the locks are used to lift ships to reach Gatun Lake and then lower them back to sea level. Once the water reaches the top of the lock, ships can continue to the next lock. Ships must pass through 6 locks to reach either side. The fresh water that flows out of the locks after the ships pass flow into the Pacific or Caribbean, meaning that water has to constantly be churned through the system as it will not be recycled and reutilized. Salt water is more corrosive than fresh water, which is the reason for the reliance on fresh water. The video below shows how the lock closes.

Each lock takes up to ten minutes to fill with water after the entry gate closes, and must be high enough to spill over the exit gate so ships can pass. On average, it takes a ship up to 11 hours to pass from one end to the other according to the Canal Authority. Besides the locks, ships must park in Gatun Lake to facilitate traffic flow. Though the canal has several lanes from one end to the other, once ships arrive at the Culebra Cut (the narrow middle passage) it becomes a one-lane passageway. This is the reason why there are designated time slots for Pacific-to-Caribbean and Caribbean-to-Pacific traffic flow as I mentioned earlier.

After we left Miraflores Lock, we headed for the second lock: Pedro Miguel. This is the newest lock and it was built by Panamanians. Alongside us on our entire trip through the canal was a large cargo ship that was never far from our vantage point.

Once we reached the Culebra Cut, we headed for a dock to depart from the ship and took a bus back to the city. The canal is a fascinating economic linkage that serves ships from over 170 countries, sees almost 14,000 ships pass through it annually, and is one of the most vital stretches of water on earth. Not to mention, it is one of Panamá’s biggest economic drivers. The implementation of tariffs on foreign goods to the United States, one of the largest destination countries for foreign ships passing through the canal, has resulted in a decrease in shipping traffic. However, the canal still handles an impressive average of 33.7 ships per day despite the economic uncertainty.

The biggest threats to the canal are actually environmental rather than economic. Deforestation along the canal has been a significant issue since its inception. Deforestation means less trees hold onto soil and during heavy rains landslides can occur that affect the canal. Terraced hillsides are a common site to help mitigate these slides. However, deforestation and a warming climate also leads to more erratic rainfall. The fact that rains in the highlands and in Gatun Lake are the engine of the system, less reliable rain presents a huge problem. Droughts have stalled some operations in the recent past, resulting in the Panamanian government building out more reservoirs to ease pressure on Gatun. The impact of environmental issues effect not only Panamá, but given the importance of the canal, the world as well.

This waterway is an amazing feat of engineering and a fascinating example of the importance and impact of linkages. If you visit Panamá, you would be remiss not to tour this incredible place. Stay tuned for the next post and be sure to like, comment, and subscribe to Traveling While Introverted so you don’t miss it!

Leave a reply to Panamá City: The Cosmopolitan Heart of the Isthmus – Traveling While Introverted Cancel reply